Early indology of india

PART 1

| early indologists & indology of india Early Indologists – a Study in Motivation The First Pioneers of Indology "The Holy Church should have an abundant number of Catholics well versed in the languages, especially in those of the infidels, so as to be able to instruct them in the sacred doctrine." The result of this was the creation of the chairs of Hebrew, Arabic and Chaldean at the Universities of Bologna, Oxford, Paris and Salamanca. A century later in 1434, the General Council of Basel returned to this theme and decreed that – "All Bishops must sometimes each year send men well-grounded in the divine word to those parts where Jews and other infidels live, to preach and explain the truth of the Catholic faith in such a way that the infidels who hear them may come to recognize their errors. Let them compel them to hear their preaching." 1 Centuries later in 1870, during the First Vatican Council, Hinduism was condemned in the "five anathemas against pantheism" according to the Jesuit priest John Hardon in the Church-authorized book, The Catholic Catechism. However, interests in indology only took shape when the British came to India. A Short History of the British in India It was the Portuguese and the Dutch who were the first Europeans to arrive in India. When the French and the British came on the scene, all parties began vying for commercial power over India’s ports. Through financial aid from their governments, treaties with local rulers and huge armies of mercenaries, the foreign trading companies gradually became more powerful than the deteriorating Moghul empire. The turning point came in 1757 when the British East India Company defeated an Indian army at the Battle of Plassey, and thus gained supremacy. Through treaties and annexation, the Company soon took full control of the subcontinent and ceded it to the British government. At first, the British government remained cautious in forcing any religious change upon the Indians. This policy seemed to be practical in ruling several hundred million Indians without sparking off a rebellion. Or as one tea-dealer Mr.Twinning put it - "As long as we continue to govern India in the mild, tolerant spirit of Christianity, we may govern it with ease; but if ever the fatal day should arrive, when religious innovation shall set her foot in that country, indignation will spread from one end of the Hindustan to the other, and the arms of fifty millions of people will drive us from that portion of the globe, with as much ease as the sand of the desert is scattered by the wind".

"Christianity had nothing to teach Hinduism, and no missionary ever made a really good Christian convert in India. He was more anxious to save the 30,000 of his country-men in India than to save the souls of all the Hindus by making them Christians at so dreadful a price". Thus, under the authority of Lord Cornwallis (1786-1805) a mood of laissez-faire dominated the British attitude towards the Indian and his religious practices. The Governor-general in 1793 had decreed to - "…preserve the laws of the Shaster and the Koran, and to protect the natives of India in the free exercise of their religion." However, one year before this law was put into effect, the author Charles Grant wrote, "The Company manifested a laudable zeal for extending, as far as its means went, the knowledge of the Gospel to the pagan tribes among whom its factories were placed." In 1808 he described the opening of Christian missionary schools and translations of the Bible into Indian languages as "principal efforts made under the patronage of the British government in India, to impart to the natives a knowledge of Christianity." Despite this, the British showed little interest in Vedic scriptures. Doubtless this was in part a reflection of the usual British attitude to India during most of the period of the Raj - that India was simply a profitable nuisance. Back home in England the various political parties had different opinions in how India should be managed. The Conservatives, though they accepted that to overthrow Indian tradition would be a difficult task, were interested in improving the Indian way of life, but stressed extreme caution for fear of an uprising. The Liberal party felt the gradual necessity of introducing western standards and values into India. The Rationalists had a more radical approach. Their belief was that reason could abolish human ignorance, and since the West was the champion of reason, the East would profit by its association. It would be accurate to say that to the 18th century Englishmen, religion meant Christianity. Of course, racism played its part also. This attitude of Europeans toward Indians was due to a sense of superiority - a cherished conviction that was shared by every Englishman in India, from the highest to the lowest. Upon his arrival in 1810, the Governor-general Marquis of Hastings wrote: "…the Hindoo appears a being merely limited to mere animal functions, and even in them indifferent...with no higher intellect than a dog..." European Evangelism in India: William Carey ‘By his [Playfair's] attempt to uphold the antiquity of Hindu books against absolute facts, he thereby supports all those horrid abuses and impositions found in them, under the pretended sanction of antiquity....Nay, his aim goes still deeper; for by the same means he endeavors to overturn the Mosaic account, and sap the very foundation of our religion: for if we are to believe in the antiquity of Hindu books, as he would wish us, then the Mosaic account is all a fable, or fiction.’ 2 Seeing India as an unlimited field for missionary activity, and insisting that it was part of a Christian government's duty to promote this, Christian missionaries came to India without any government approval.

Carey and his colleagues experimented with what came to be known as Church Sanskrit. He wanted to train a group of 'Christian Pandits' who would probe "these mysterious sacred nothings" and expose them as worthless. He was distressed that this "golden casket (of Sanskrit) exquisitely wrought" had remained "filled with nothing but pebbles and trash." He was determined to fill it with "riches - beyond all price," that is, the doctrine of Christianity. 4 In fact, Carey smuggled himself into India and caused so much trouble that the British government labeled him as a political danger. After confiscating a batch of Bengali pamphlets printed by Carey, the Governor-general Lord Minto described them as – "Scurrilous invective…Without arguments of any kind, they were filled with hell fire and still hotter fire, denounced against a whole race of men merely for believing the religion they were taught by their fathers." Unfortunately Carey and other preachers of his ilk finally gained permission to continue their campaigns without government approval. Other Preachers "The plain truth concerning the mass of the [Indian] population — and the poorer classes alone — is that they are not civilized people." Reverend A.H. Bowman wrote that Hinduism was a – "…great philosophy which lives on unchanged whilst other systems are dead, which as yet unsupplanted has its stronghold in Vedanta, the last and the most subtle and powerful foe of Christianity." In 1790, Dr.Claudius Bucchanan, a missionary attached to the East India Company, arrived in Bengal. Not long after his arrival, the good doctor stated- "Neither truth, nor honesty, honor, gratitude, nor charity, is to be found in the breast of a Hindoo."

"The whole history of this famous god (Krsna) is one of lust, robbery, deceit and murder…the history of the whole hierarchy of Hindooism is one of shameful iniquity, too vile to be described." The prominent missionary, Alexander Duff (1806-1878) founded the Scottish Churches College, in Calcutta, which he envisioned as a "headquarters for a great campaign against Hinduism." Duff sought to convert the Indians by enrolling them in English-run schools and colleges, and placed emphasis on learning Christianity through the English language. Duff wrote - " While we rejoice that true literature and science are to be substituted in place of what is demonstrably false, we cannot but lament that no provision has been made for substituting the only true religion-Christianity - in place of the false religion which our literature and science will inevitably demolish… Of all the systems of false religion ever fabricated by the perverse ingenuity of fallen man, Hinduism is surely the most stupendous." Duff received remarkable success in his educational and missionary activities amongst the higher classes in Calcutta. The number of students in the mission schools was four times higher than that in government schools. It is an axiomatic truth that the aim of missionaries like Duff was not so much education than conversion. They were obliged to use the excuse of education in order to meet he needs of the converted population, and more importantly, to train up Indian assistants to help them in their proselytizing. Duff remained unsatisfied with converting Indians belonging to low-castes and orphans – his chosen target was the higher castes, specifically the brahmanas, in order to accelerate the demise of Hinduism. Many Englishmen patronized missionary schools such as Duffs. Charles Trevelyan, an officer with the East India Company asserted in a widely circulated tract- " The multitudes who flock to our schools ... cannot return under the dominion of the Brahmins. The spell has been forever broken. Hinduism is not a religion that will bear examination... It gives away at once before the light of European sciences." J.N. Farquhar, a Scottish clergyman, preached in India from 1891 to 1923, during which time he wrote a book called The Crown of Hinduism. In this work he says that although Hinduism may have some good points, ultimately true salvation can only be achieved through Christ, who is the ‘crown of Hinduism’. Reverend William Ward, an English missionary, wrote a four-volume polemic in which he characterized the Hindu faith as "a fabric of superstition" concocted by Brahmins, and as "the most complete system of absolute oppression that perhaps ever existed". Richard Temple, a high officer, said in an 1883 speech to a London missionary society: " India presents the greatest of all fields of missionary exertion... India is a country which of all others we are bound to enlighten with external truth...But what is most important to you friends of missions, is this - that there is a large population of aborigines, a people who are outside caste....If they are attached, as they rapidly may be, to Christianity, they will form a nucleus round which British power and influence may gather." He addressed a mission in New York in bolder terms: "Thus India is like a mighty bastion which is being battered by heavy artillery. We have given blow after blow, and thud after thud, and the effect is not at first very remarkable; but at last with a crash the mighty structure will come toppling down, and it is our hope that someday the heathen religions of India will in like manner succumb." Indian religion was thus perceived by the British missionaries as an enemy waiting to be conquered by the army of Jesus. It was a doctrine of Satan which provided Christianity with devils to exorcise and which, in their view, was "at best, work of human folly and at worst the outcome of a diabolic inspiration." 5 In the word of Charles Grant (1746-1823), Chairman of the East India Company: "We cannot avoid recognizing in the people of Hindustan a race of men lamentably degenerate and base...governed by malevolent and licentious passions...and sunk in misery by their vices." One Professor McKenzie, of Bombay found the ethics of India defective, illogical and anti-social, lacking any philosophical foundation, nullified by abhorrent ideas of asceticism and ritual and altogether inferior to the 'higher spirituality' of Europe. He devoted most of his book 'Hindu Ethics' to upholding this thesis and came to the conclusion that Vedic philosophical ideas, 'when logically applied leave no room for ethics'; and that they prevent the development of a strenuous moral life.' All efforts were made by the missionaries to portray Hinduism as backwards, illogical, debauched and perverse. As one preacher exclaimed, 'The curse of India is the Hindoo religion. More than two hundred million people believe a monkey mixture of mythology that is strangling the nation.' 'He who yearns for God in India soon loses his head as well as his heart.' The missionaries opposed the government’s efforts to take a neutral stand towards Indian culture and worked with more zeal for the complete conversion of the natives. Thus India became an arena for religious adventure. The First Scholars: Sir William Jones "I am in love with Gopia, charmed with Crishen (Krishna), an enthusiastic admirer of Raama and a devout adorer of Brihma (Brahma), Bishen (Vishnu), Mahisher (Maheshwara); not to mention that Judishteir, Arjen, Corno (Yudhishtira, Arjuna, Karna) and the other warriors of the M'hab'harat appear greater in my eyes than Agamemnon, Ajax and Achilles apperaed when I first read the Iliad" 6 However, Jones was a devout Christian and could not free himself of the restraints of Biblical chronology. His theories of dating Indian history, specifically Candragupta Maurya’s reign up to the invasions of India by Alexander were certainly dictated to him through religious bias. He also described the Srimad Bhagavatam as "a motley story" and claimed that it had it’s roots in the Christian Gospels, which had been brought to India and, ‘repeated to the Hindus, who ingrafted them on the old fable of Ce’sava, (Kesava)’. Of course, this theory has been debunked since records of Krsna worship predate Christ by centuries. (See Heliodorus Column) In 1840 Jones was appointed Chief Justice in the British settlement of Fort William. Here, in 1846, he translated into English the famous play ‘Sakuntala’ by Kalidasa and ‘The Code of Manu’ in 1851, the year of his death. After him, his younger associate, Sir Henry Thomas Colebrooke, continued in his stead and wrote many articles on Hinduism. The eminent British historian James Mill (father of the philosopher John Stuart Mill) who had published his voluminous History of British India in 1818 heavily criticized Jones. Although Mill spoke no Indian languages, had never studied Sanskrit, and had never been to India, his damning indictment of Indian culture and religion had become a standard work for all Britishers who would serve in India. Mill vehemently believed that India had never had a glorious past and treated this as an historical fantasy. To him, Indian religion meant, ‘The worship of the emblems of generative organs’ and ascribing to God, ‘…an immense train of obscene acts.’ Suffice to say that he disagreed violently with Jones for his ‘Hypothesis of a high state of civilization.’ Mill’s History of British India was greatly influenced by the famous French missionary Abbe Dubois’s book Hindu Manners, Customs and Ceremonies. This work, which still enjoys a considerable amount of popularity to this day, contains one chapter on Hindu temples, wherein the Abbe writes: "Hindu imagination is such that it cannot be excited except by what is monstrous and extravagant." H.H. Wilson "Mill’s view of Hindu religion is full of very serious defects, arising from inveterate prejudices and imperfect knowledge. Every text, every circumstance, that makes against the Hindu character, is most assiduously cited, and everything in its favor as carefully kept out of sight, whilst a total neglect is displayed of the history of Hindu belief."7 Wilson seemed somewhat of an enigma; on one hand he proposed that Britain should restrain herself from forcing Christianity upon the Indians and forcing them to reject their old traditions. Yet in the same breath he exclaimed: "From the survey which has been submitted to you, you will perceive that the practical religion of the Hindus is by no means a concentrated and compact system, but a heterogeneous compound made up of various and not infrequently incompatible ingredients, and that to a few ancient fragments it has made large and unauthorized additions, most of which are of an exceedingly mischievous and disgraceful nature. It is, however, of little avail yet to attempt to undeceive the multitude; their superstition is based upon ignorance, and until the foundation is taken away, the superstructure, however crazy and rotten, will hold together." Wilson’s view was that Christianity should replace the Vedic culture, and he believed that full knowledge of Indian traditions would help effect that conversion. Aware that the Indians would be reluctant to give up their culture and religion, Wilson made the following remark:

Wilson felt hopeful that by inspired, diligent effort the "specious" system of Vedic thought would be "shown to be fallacious and false by the Ithuriel spear of Christian truth. He also was ready to award a prize of two hundred pounds "…for the best refutation of the Hindu religious system." Wilson also wrote a detailed method for exploiting the native Vedic psychology by use of a bogus guru-disciple relationship. Recently Wilson has been accused of invalid scholarship. Natalie P.R. Sirkin has presented documented evidence, which shows that Wilson was a plagiarist. Most of his most important works were collected manuscripts of a deceased author that he published under his own names, as well as works done without research. Thomas Babbington Macaulay As to the value of teaching Sanskrit and India’s classical literatures, as well as regional languages, in schools to be established by the British for the education of the Indian people, A few members of the Council were mildly in favor of it, but the elegantly expressed, fully ethnocentric and Philistine view of Macaulay prevailed. In his Education Minute, Macaulay wrote that he couldn’t find one Orientalist.

He went on to make the outrageous assertion that – "…all the historical information which has been collected from all the books written in the Sanscrit language is less valuable than what may be found in the most paltry abridgements used in preparatory schools in England." He then made the following creatively expressed, though uneducated assertion as his central statement of belief –

In a letter to his father in 1836, Macaulay exclaimed – "...It is my belief that if our plans of education are followed up, there will not be a single idolator among the respectable classes in Bengal thirty years hence. And this will be effected without any efforts to proselytize, without the smallest interference with religious liberty, by natural operation of knowledge and reflection. I heartily rejoice in the project." In other words, Lord Macaulay believed that by knowledge and reflection, the Hindus would turn their backs upon the religion of their forefathers and take up Christianity. In order to do this, he planned to use the strength of the educated Indians against them by using their scholarship to uproot their own traditions, or in his own words - " Indian in blood and color, but English in taste, in opinion, in morals, in intellect." He firmly believed that, "No Hindu who has received an English education ever remains sincerely attached to his religion." To further this end Macaulay wanted a competent scholar who could interpret the Vedic scriptures in such a manner that the newly educated Indian youth would see how barbaric their native superstitions actually were. Macaulay finally found such a scholar in Fredrich Max Mueller. |

india indology continues with Part 2 — Max Mueller . . .

It may be surprising to learn that the first pioneer in indology was the 12th Century Pope, Honorius IV. The Holy Father encouraged the learning of oriental languages in order to preach Christianity amongst the pagans. Soon after this in 1312, the Ecumenical Council of the Vatican decided that-

It may be surprising to learn that the first pioneer in indology was the 12th Century Pope, Honorius IV. The Holy Father encouraged the learning of oriental languages in order to preach Christianity amongst the pagans. Soon after this in 1312, the Ecumenical Council of the Vatican decided that-

Another point of view in support of that policy was by Montgomery.

Another point of view in support of that policy was by Montgomery.

Bucchanan traveled to Puri in Orissa and witnessed the annual Ratha-yatra (or as Bucchanan called it, ‘The horrors of Juggernaut’). His description of Jagannatha – ‘The Indian Moloch’, has been recorded by the historian George Gogerly as- "…a frightful visage painted black, with a distended mouth of bloody horror." Perhaps, by seeing the face of Lord Jagannatha, the British hallucinated and saw a projection of their own international destiny of bloodshed and carnage. In any case, from the time the British observed the ‘terrifying’ sight of the Lord on His gigantic chariot, the word ‘juggernaut’ entered the English language and became synonymous with any great force that crushes everything in its path. Gogerly went on to write –

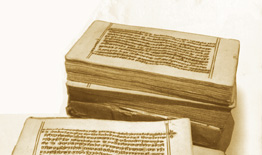

Bucchanan traveled to Puri in Orissa and witnessed the annual Ratha-yatra (or as Bucchanan called it, ‘The horrors of Juggernaut’). His description of Jagannatha – ‘The Indian Moloch’, has been recorded by the historian George Gogerly as- "…a frightful visage painted black, with a distended mouth of bloody horror." Perhaps, by seeing the face of Lord Jagannatha, the British hallucinated and saw a projection of their own international destiny of bloodshed and carnage. In any case, from the time the British observed the ‘terrifying’ sight of the Lord on His gigantic chariot, the word ‘juggernaut’ entered the English language and became synonymous with any great force that crushes everything in its path. Gogerly went on to write – Sir William Jones (1746-1794) was the first Britisher to learn Sanskrit and study the Vedas. He was educated at Oxford University and it was here that he studied law and also began his studies in oriental languages, of which he is said to have mastered sixteen. After being appointed as judge of the Supreme Court, Jones went to Calcutta in 1783. He founded the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal and translated a number of Sanskrit texts into English. Jones was not prone to criticize other religions, especially the Vedic religion, which he respected and adored. He wrote –

Sir William Jones (1746-1794) was the first Britisher to learn Sanskrit and study the Vedas. He was educated at Oxford University and it was here that he studied law and also began his studies in oriental languages, of which he is said to have mastered sixteen. After being appointed as judge of the Supreme Court, Jones went to Calcutta in 1783. He founded the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal and translated a number of Sanskrit texts into English. Jones was not prone to criticize other religions, especially the Vedic religion, which he respected and adored. He wrote –

No comments:

Post a Comment